This article was published in TSE science magazine, TSE Mag. It is part of the Autumn 2024 issue, dedicated to health. Discover the full PDF here and email us for a printed copy or your feedback on the mag, there.

Healthy eating offers powerful protection against the world’s biggest killers. It dramatically reduces the risk of non-communicable chronic diseases (NCDs) – such as heart conditions, diabetes and cancer – that account for three quarters of global deaths. We asked TSE experts on the economics of food, health and obesity about how to eat better.

WHAT’S WRONG WITH ULTRA-PROCESSED FOOD?

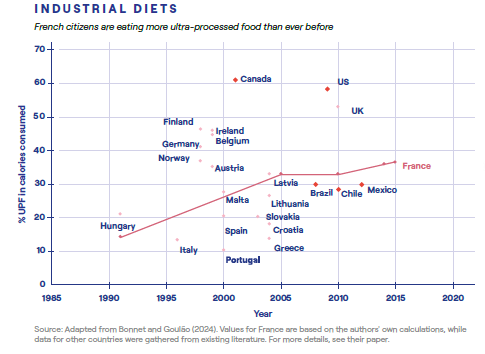

CATARINA GOULÃO : Most food is processed to some extent but today’s industrial transformations generally have too much salt, fat, and sugar, not enough fiber and vitamins, and are linked to obesity and NCDs. Ultra processed foods (UPFs) are an increasingly large part of our diets, 36% in 2015 against 14% in early 90s.

Comparing French families over 10 years, we found UPF consumption is linked to obesity, poverty, rural, northern and eastern regions. Within households, only drastic changes such as the arrival of young children or becoming single appear to encourage UPF-consumption. Our data also suggests younger generations eat more UPF food because their preferences have been warped by greater exposure to UPFs. If so, the table is set for French diets to get even worse.

HOW CAN GOVERNMENTS IMPROVE OUR DIETS?

CÉLINE BONNET: Food labels and recommendation campaigns are common policy tools. Pierre Dubois and I found that France’s Nutriscore label successfully promoted highly nutritional products. But sin taxes (see below) and other policies may be better suited for discouraging junk food. For instance, my research with Valérie Orozco calls for restrictions on fast-food restaurants because they are linked to higher local obesity. Catarina Goulão with Helmuth Cremer and Jean-Marie Lozachmeur have shown that taxing grams of sugar needs to be combined with taxing litres of soda to account for the industry's product reformulation in response to taxes.

Taxes on specific junk foods can be undermined by firms and consumers switching to equally unhealthy products. A tax on sugary drinks may increase consumption of cookies, for example, or a tax on sugar may encourage the food industry to add more salt, fat and artificial sweeteners of doubtful health consequences.

Policies that take aim at UPFs in general – such as Colombia’s tax on products laden with sugar, salt and fat – are likely to be more effective. We show that consumers switch to non-UPF options when all UPFs get more expensive. Governments should also target vulnerable populations like the young and poor, as they seem particularly receptive to price changes.

Sin taxes aim to reduce consumption of ‘harmful’ goods – such as alcohol, tobacco, UPFs, or gambling – by increasing their price.